BOSTON – HOME OF THE 1872 WORLD PEACE JUBILEE

PATRICK SARSFIELD GILMORE

For 18 days in the summer of 1872, Boston was the musical center of the universe, the City on a Hill that inspired the world.

Boston was the setting for the World Peace Jubilee and International Music Festival, said to be the largest concert in the history of the world. It started on June 17, Bunker Hill Day, and ended on the Fourth of July, and in that time over 2,000 musicians and 20,000 singers came together, in various ensembles and also en masse, to convey the joy, comfort and inspiration that music can bring.

The man behind the festival was Patrick S. Gilmore, a gifted cornet player, bandleader and impresario who had devoted his life to the audacious dream that music had the power to change the world, that it could be used as an instrument of peace.

Gilmore, who emigrated from Ireland in 1849, was a band master in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and knew first hand the transformative power of music. He had conducted large scale concerts in New Orleans in 1864 and Boston’s National Peace Jubilee in 1869 to celebrate peace in the aftermath of the Civil War.

And now, with Europe’s Franco-Prussian War ending in 1871, Gilmore wanted musicians from the warring nations to come together to create “a union of all nations in harmony, to sing, as never before, the hymn of the angels: peace on earth, and good will towards all men.”

He sailed to Europe and visited the capital cities and royal courts, persuading kings and presidents to send their finest musicians to Boston. London agreed to send the Grenadier Guards and Paris the La Garde Republicaine. The Germans would send the Kaiser Franz Regiment and the Kaiser’s personal band, the Cornet Quartet.

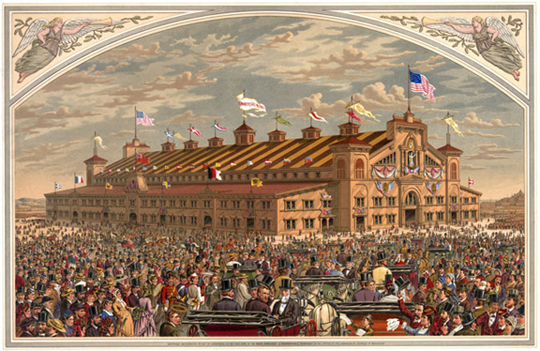

In Boston contractors began building a massive, temporary coliseum to hold 60,000 spectators and 22,000 musicians. Built on vacant railroad land in Back Bay, close to where Copley Square is today, the coliseum was 550 x 350 feet, larger than a football field. Inside it was fashioned as an amphitheatre, with balconies 75 feet deep.

As June 17 neared, Boston was abuzz. Painters put finishing touches on the coliseum, nicknamed the Temple of Peace. Marching bands paraded on Boston Common. Musicians dashed around town with their sheet music, while school children practiced in class rooms and church halls.

People began pouring into the city by train, boat and horse carriage from across the nation. Hotels were filled, restaurants were bustling. President Grant, who had attended the 1869 Jubilee, announced he was returning for the Jubilee, causing great excitement. On opening day, “The sun was bright and the sky was blue,” reported a newspaper. Even the weather cooperated.

But in the end, it was not the weather or the excitement that made the greatest impact. It was the music.

The Jubilee featured classical music by Bach, Mendelssohn, Mozart and Handel. Sacred hymns like To God on High and Gloria were played with reverence. Patriotic American songs like the Star Spangled Banner were played every day. Irish songs like The Last Rose of Summer received hearty encores.

Years later, people still talked about three Festival highlights in particular:

• Johann Strauss, the Austrian waltz king, made his American debut at the Jubilee, having met Gilmore in Vienna the previous summer. Strauss conducted his famous waltz, the Beautiful Blue Danube, to thunderous applause, and also composed a Jubilee Waltz especially for the occasion, dedicated to Gilmore.

• The Fisk Jubilee Singers, a group of Black college students from Fisk University in Nashville, performed at the Jubilee, “sending the audience into a rapture of boisterous enthusiasm” for its rendition of Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory of the Coming of the Lord. President Grant invited them to perform at the White House later that year, helping to launch a singing ensemble that still flourishes today.

• The unlikely stars of the Jubilee were the 100 Boston firemen, dressed resplendent in red shirts and white suspenders, whose job it was to hammer onto 100 anvils as part of the chorus to Verdi’s Il Trovatore (The Troubadour). As the firemen hammered in unison, cannons outside the coliseum were firing and all of Boston’s church bells were ringing as the orchestra reached a crescendo.

Patrick S. Gilmore went on to become one of the most celebrated band leaders of the 19th century. And for 18 days in 1872, he made Boston a true City on the Hill.

(My thanks to the late Michael Cummings for providing some of this information.)

- Michael P. Quinlin

© Boston Irish Tourism Association